One of the reasons the conflict that I call the Texas Revolution of 1811 has long languished in historical obscurity is the lack of primary sources. Only about a half dozen first-hand accounts, some fragmentary, provide an accurate history of the conflict. The three most in-depth of these are the Warren D.C. Hall account, the McLane account and that of Carlos Beltrán.

Hall's account has long been known, but the other two were lost for over a century before their rediscovery. They are highly useful when considered together, as McLane’s account covers the period from August 1812 to July 1813 and Beltrán’s covers the period from April to August 1813.

McLane’s account was first published in an obscure, unionist newspaper in

San Antonio in the 1860s, and was lost for about 100 years, before being

rediscovered. Beltrán’s account, written by the author in Mexico, also around

the 1850s-60s, was discovered there by an American consul, who gave it to

publisher John Warren Hunter of the history magazine “Frontier Times,” who

published it in the 1920s and 1940s.

|

| The Beltrán account first appeared serialized in the Oct., Nov. and Dec. 1925 editions of the Frontier Times. |

Beltrán’s account, which was actually rediscovered first, was greeted skeptically by many historians. It is detailed and in very many ways romantic. It is told from the perspective of a young American, a veteran of the Burr Conspiracy, who continued on to Texas and settled there in 1807. Accepted into a Tejano family, he became in great part Mexicanized - so much, in fact, that his account was originally in Spanish. He claimed that he found work as a gunsmith in San Antonio, serving the Spanish Army from 1807-12.

Beltrán’s identity is mysterious. His name, he admits in his

memoir, was adopted by him as a “translation” of his original American name,

which he never reveals. No record of him can be traced in the Béxar Archives,

but there does exist a man with an almost identical biography – an American

gunsmith in the Spanish service named Daniel Boone (not to be confused with the

famous pioneer of the same name). Boone and Beltrán are about the same age, and

Boone arrived in Texas a year before Beltrán claimed he did. Beltrán ultimately

retired to Mexico and lived many years after the expedition.

Beltrán may be Boone, writing under a pseudonym, and

possibly wanted to keep his participation in the filibuster a secret.

Alternatively, he may have been an acquaintance who appropriated Boone’s

identity to conceal his own. Neither man is mentioned in other accounts of the

expedition, although a young boy about 12 years old named “Peter Boon” is so

noted and was reported to have been captured at Medina. He too, like Beltrán,

later settled in Mexico.

The Case for the Beltrán Account

As for Beltrán’s account of the expedition, it is colorful,

precise, and even romantic. For this latter reason, some historians have

questioned its veracity, some even suggesting it is an invention of Frontier

Times editor John Warren Hunter in the 20th Century. It is at least partly

authentic, however. It was published first in the 1920s before any of the other

detailed primary accounts were generally known, (Hall's account existing, but not published) and before the first published

book on the subject. Its aligns very well with McLane’s narrative, even though

his account was lost to history until the 1960s, long after Beltrán’s account

was written.

A modern reader attempting to determine its veracity must put himself back into the time period in which it was written. There were very few primary source documents from which any forgery could have been drawn, and all accounts in 19th Century histories were very thin on details. Beltrán, however, calls to mind many details that only someone who was there, or had access to many other primary sources widely scattered, could have known. Bear in mind, most of the names of participants were never printed in the sketchy accounts available at the time. The evidence shows the account is genuine.

Beltrán knows too many Americans to be a Mexican forger, and too many Mexicans to be an American one. It is certainly possible that the story, while mostly true, is embellished. He could have dramatized events, or placed himself in a first-person position for something he really only heard second hand. But crucially he does not do this for one of the most dramatic events he reports, the murder of the royalists.

Read critically with other sources lined up side-by-side, the account “rings” true as that of someone who was in San Antonio at the time he claims he was. He has information in no other accounts, and then has information in one account but not another, and the matching accounts are not always the same one. Here is one very strong example. Before the execution of the royalist officers, when the Anglo-American contingent is in uproar about the sentence of death, Bernardo Gutiérrez suddenly offers to send them to the coast and into exile instead. This story only exists in three places, crucially in Beltran, McLane (who effectively post-dates Beltran), and in the obscure (in the 1920s) Bullard account. This is how the accounts square up side-by-side.

There are many instances in the account where the writer's knowlege is precise and highly accurate, but there is one obscure detail that proves without a doubt that the account is genuine: Beltrán in his account places the uniquely named Orramel Johnston as a participant in the expedition. This is crucial, because of all the other first hand and even second-hand accounts, including Villars, Hall, McLane, or the various individuals who wrote letters to William Shaler, none ever mentioned Orramel Johnston, though several of them mentioned his brother Darius. However, Orramel - whose name is so unique it is impossible to imagine it being invented without a true source - did indeed participate. The document proving it, and indeed the only other account that establishes Orramel in Texas is a Johnston family genealogy written in 1897 – long after Beltrán (whoever he was) had died. It is significantly obscure that no author writing on this topic in since 1897 found it prior to myself stumbling upon it in a Google search in 2016 after the rare book was digitized. Moreover, Beltrán not only places him in the expedition, but correctly records that he was a trained physician.

|

| Beltrán’s account, mentioning Dr. Orramel Johnston, as being the intended recipient of the condemned Spanish prisoner's watch and ring. |

Who was Beltrán?

Beltrán’s identity is unprovable at this time, though the most likely connection is the Boone one, noted above. In his autobiographical section of his account, he also mentions a visit to Mexico in 1807 in the company of General James Wilkinson’s agent Walter Burling. The latter was a real man who visited Mexico on a secret mission at precisely this time. His aim was to visit Spanish officials on behalf of the treasonous General James Wilkinson, who almost certainly took a Spanish bribe to defeat the Burr Conspiracy. Burling’s mission – undoubtedly connected to this bribe – was, moreover, only well-known in the United States in 20th Century accounts of Wilkinson’s treason.

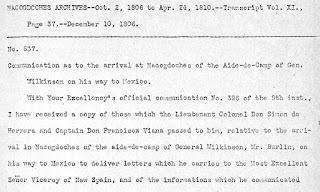

|

| Spanish account of the arrival of Walter Burling on a secret mission, referenced in the Beltran account. |

On this trip, Beltrán claimed to have met Zebulon Pike, returning from his imprisonment in Mexico. Pike leaves his own account of this trip, which allows a cross-check. At the Rio Grande, Pike records meeting two Americans. One is a man named Griffith, who is an American deserter in the Spanish service. This would align very well, since Beltrán claimed he was an acolyte of Burr who came to Texas rather than return home after the conspiracy failed, which is a very likely action for someone who was running from justice. Additionally, we know that while the Spanish generally sent captured Americans back to their home country, they often made exceptions for deserters, particularly if they had a skill and desire to serve the Spanish.

The other American Pike met in Mexico was in Pike’s account a man possibly affiliated with Burr and originally from Virginia. Beltrán, in his

account, claimed to be a native of Wheeling, Virginia (today’s West Virginia).

Pike claims his soldiers recognized the man as a murderer and denounced him to

Spanish authorities. Another reason to be running from the United States. It is

interesting to note that in Beltrán’s account, he takes great pleasure in

noting how many of the American filibusters are running from justice in one

form or another. Is he truly affronted by them, or was he secretly just like

these men he criticized?

Was Beltrán in fact Daniel Boone (or Peter) writing under a

pseudonym? Was he a deserter or a murderer reinventing himself by stealing

Boone’s biography for his own? Whether it was these or any other scenario, the

American’s account, as the evidence indicates, is at least partly true,

although it certainly conceals something. It remains one of the most

interesting, and elusive, mysteries of the war.

John Warren Hunter, “Some Early Tragedies of San Antonio,”

Frontier Times, 18 No. 3 (Dec. 1940), 115. Johnston, 54. Orsi, 236. McDonald,

25. “P Boon” account by Villars in Charles Adams Gulick, Jr. The Papers of

Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar 6 Vol. (Austin: The Pemberton Press, 1968),

4(1):261.

No comments:

Post a Comment